USS Wasp (CV-7)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other vessels sharing the same name, see USS Wasp.

This article comprises a range of references; however, the sources are not clear as it lacks adequate inline citations. Please assist in enhancing this article by integrating more accurate citations. (March 2010)

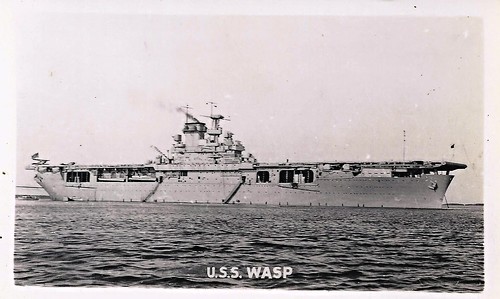

USS Wasp (CV-7).jpg

USS Wasp entering Hampton Roads

Class overview

Name: Wasp-class aircraft carrier

Operators: United States Navy

Preceded by: Yorktown class

Succeeded by: Essex class

Built: 1936–40

In commission: 1940–42

Planned: 1

Completed: 1

Lost: 1

History

United States

Name: Wasp

Namesake: USS Wasp (1814)

Ordered: 19 September 1935

Builder: Fore River Shipyard

Laid down: 1 April 1936

Launched: 4 April 1939

Sponsored by: Mrs. Charles Edison[1]

Commissioned:

25 April 1940

(first Commanding Officer: Captain John W. Reeves, Jr.)

Struck: 15 September 1942

Honors and

awards: American Defense Service Medal (“A” device) / American Campaign Medal/European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal (1 star) / Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal (1 star) / World War II Victory Medal

Fate: Sunk by IJN I-19, 15 September 1942

General characteristics

Type: Aircraft carrier

Displacement:

As built: 14,700 long tons (14,900 t) (standard)

19,116 long tons (19,423 t) (full load)

Length:

688 ft (210 m) (waterline)

741 ft 3 in (225.93 m) (overall)

Beam:

80 ft 9 in (24.61 m) (waterline)

109 ft (33 m) (overall)

Draft: 20 ft (6.1 m)

Installed power: 70,000 shp (52,000 kW)

Propulsion:

2 × Parsons steam turbines

6 × boilers at 565 psi

2 × shafts

Speed: 29.5 kn (54.6 km/h; 33.9 mph)

Range: 12,000 nmi (22,000 km; 14,000 mi) at 15 kn (28 km/h; 17 mph)

Complement:

1,800 officers and men (peacetime)

2,167 (wartime)

Sensors and

processing systems: CXAM-1 radar[2]

Armament:

As Built:

8 × 5 in (130 mm)/38 cal guns

16 × 1.1 in (28 mm)/75 cal anti-aircraft guns

24 × .50 in (13 mm) machine guns

Armor:

As Built:

60 lb (27 kg) STS conning tower

3.5 in side and 22 ft 6 in (6.86 m)50 lb deck over steering gear

Aircraft carried: As built: Up to 100

Aviation facilities:

3 × elevators

4 × hydraulic catapults (2 flight deck, 2 hangar deck)

USS Wasp (CV-7) served as a United States Navy aircraft carrier that was commissioned in 1940 and lost in combat in 1942. She was the eighth vessel to carry the name USS Wasp and was the only ship of a class created to utilize the remaining tonnage permitted to the U.S. for aircraft carriers under the treaties of that era. As a downsized variant of the Yorktown-class aircraft carrier design, Wasp was more susceptible than other American aircraft carriers at the onset of hostilities. Initially engaged in the Atlantic campaign, where Axis naval forces were viewed as less capable of delivering decisive blows, Wasp later supported the occupation of Iceland in 1941 before joining the British Home Fleet in April 1942, transporting British fighter aircraft to Malta twice. The carrier was subsequently assigned to the Pacific in June 1942 to compensate for losses sustained during the battles of Coral Sea and Midway. After aiding the invasion of Guadalcanal, Wasp was lost to the Japanese submarine I-19 on 15 September 1942.

Contents

1 Design

2 Service history

2.1 Inter-war period

2.2 World War II

2.2.1 Atlantic Fleet

2.2.2 Pacific Fleet

3 Loss

4 Awards

5 References

6 External links

Design

Wasp was a consequence of the Washington Naval Treaty. Following the construction of carriers Yorktown and Enterprise, the U.S. was still allocated 15,000 long tons (15,000 t) for the construction of a carrier.

Wasp was the pioneering carrier equipped with a deck edge elevator.

The Navy aimed to fit a substantial air group onto a vessel with nearly 25% less displacement than the Yorktown-class. To conserve weight and space, Wasp was designed with lower-powered machinery (comparing Wasp’s 75,000 shp (56,000 kW) powerplant to Yorktown’s 120,000 shp (89,000 kW), the Essex-class’s 150,000 shp (110,000 kW), and the Independence-class’s 100,000 shp (75,000 kW)).

Moreover, Wasp was launched with minimal armor, modest speed, and, critically, without torpedo protection. The lack of side reinforcement for the boilers and internal aviation fuel reserves “doomed her to a fiery fate”. These were embedded design flaws acknowledged during construction but could not be corrected within the specified tonnage.[3] Such shortcomings, along with a relative inexperience in damage control during the war’s early stages, ultimately proved fatal.[citation needed]

Wasp was the first carrier to be equipped with a deck edge elevator, which consisted of a platform for the front wheels and an extension for the tail wheel. The two arms on either side maneuvered the platform in a semicircle up and down between the flight deck and the hangar deck.

Service history

Inter-war period

She was laid down on 1 April 1936 at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts; launched on 4 April 1939, sponsored by Carolyn Edison (wife of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Charles Edison), and commissioned on 25 April 1940 at the Army Quartermaster Base, South Boston, Massachusetts, with Captain John W. Reeves, Jr. in command.

Wasp remained in Boston throughout May for outfitting before departing on 5 June 1940 for calibration tests on her radio direction finder equipment. Following further outfitting while anchored in Boston harbor, the new aircraft carrier independently steamed to Hampton Roads, Virginia, anchoring there on 24 June. Four days later, she set sail for the Caribbean accompanied by the destroyer Morris.

On the way, she conducted the first of numerous carrier qualification exercises. Among the initial qualifiers was Lieutenant, junior grade David McCampbell, who would later become the Navy’s top-scoring “ace” in World War II. Wasp reached Guantanamo Bay Naval Base just in time to “dress ship” in celebration of Independence Day.

A tragic incident marred the carrier’s shakedown. On 9 July, one of her Vought SB2U-2 Vindicator dive bombers crashed 2 nautical miles (2.3 mi; 3.7 km) from the ship. Wasp surged to flank speed to assist, as did the plane-guarding destroyer Morris. The latter’s boats retrieved items from the aircraft’s baggage compartment; however, the plane itself had gone down with its two crew members.

Wasp left Guantanamo Bay on 11 July and returned to Hampton Roads four days later. There, she took on aircraft from the 1st Marine Air Group and took them to sea for qualification trials. Operating off the southern drill grounds, the ship and her aircraft refined their skills for a week before the Marines and their planes disembarked at Norfolk, and the carrier moved north to Boston for post-shakedown repairs.

While in Boston, she fired a 21-gun salute and paid tribute to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whose yacht, Potomac, made a brief stop at the Boston Navy Yard on 10 August.

Wasp departed the Army Quartermaster Base on the 21st to carry out steering exercises and full-power trials. Late the following morning, she set out for Norfolk, Virginia. Over the next few days, while destroyer Ellis served as plane guard, Wasp launched and recovered her aircraft: fighters from Fighter Squadron 7 (VF-7) and scout bombers from Scouting Squadron 72 (VS-72). The carrier entered the Norfolk Navy Yard on 28 August for turbine repair work—alterations that kept her in dockyard hands into the succeeding month. She was drydocked from 12–18 September, completing her final sea trials in Hampton Roads on 26 September 1940.

Now prepared to join the fleet and assigned to Carrier Division 3, Patrol Force, Wasp transitioned to Naval Operating Base, Norfolk (NOB Norfolk) from the Norfolk Navy Yard on 11 October. There, she loaded 24 Curtiss P-40

fighters from the Army Air Corps’ 8th Pursuit Group and nine North American O-47A reconnaissance aircraft from the 2nd Observation Squadron, along with her own spare and utility unit Grumman J2F Duck flying boats on the 12th. Moving to sea for maneuvering space, Wasp launched the Army planes in a trial intended to assess the take-off distances of standard Navy and Army aircraft. This experiment marked the first instance of Army planes operating from a Navy carrier, hinting at the ship’s future role as a ferry during World War II.

Wasp then continued towards Cuba, accompanied by destroyers Plunkett and Niblack. Over the subsequent four days, the carrier’s aircraft conducted routine training flights, which included dive-bombing and machine gun drills. Upon reaching Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, Wasp’s saluting batteries discharged a 13-gun salute in honor of Rear Admiral Hayne Ellis, Commander of the Atlantic Squadron, who was aboard battleship Texas on 19 October.[1]

Throughout the remainder of October and into November, Wasp engaged in training activities in the Guantanamo Bay region. Her aircraft underwent carrier qualification and refresher training flights, while her gunners honed their skills in short-range battle exercises targeting towed by the new fleet tug Seminole.

After concluding her operations in the Caribbean, Wasp departed for Norfolk, arriving shortly after noon on 26 November. She stayed at the Norfolk Navy Yard until Christmas of 1940. Subsequently, after first conducting degaussing tests with the survey ship Hannibal, she sailed independently to Cuba.

Arriving at Guantanamo Bay on 27 January 1941, Wasp executed a standard routine of flight operations through February. With destroyer Walke serving as her plane guard, Wasp operated out of Guantanamo and Culebra, conducting her drills alongside an impressive array of warships—including battleship Texas, carrier Ranger, heavy cruisers Tuscaloosa and Wichita, and numerous destroyers. Wasp carried out gunnery drills and exercises, as well as typical flight training maneuvers into March. Underway for Hampton Roads on 4 March, the aircraft carrier conducted night battle practice that extended into the early dawn hours of the 5th.

During her transit to Norfolk, severe weather developed on the evening of 7 March. Wasp was proceeding at standard speed, 17 knots (20 mph; 31 km/h). Off Cape Hatteras, a lookout detected a red flare at 22:45, followed by a second set of flares at 22:59. At 23:29, with the assistance of her searchlights, Wasp identified the distressed vessel as the lumber schooner George E. Klinck, en route from Jacksonville, Florida, to Southwest Harbor, Maine.

The sea conditions deteriorated from a state 5 to a state 7. Wasp positioned herself, maneuvering alongside at 00:07 on 8 March. At that moment, four men from the schooner ascended a swaying Jacob’s ladder, buffeted by strong winds. Then, despite the fierce storm, Wasp lowered a boat at 00:16 and rescued the remaining four men from the floundering 152 ft (46 m) schooner.[1]

Later that day, Wasp disembarked her rescued sailors and promptly entered drydock at the Norfolk Navy Yard. The vessel underwent essential repairs to her turbines. Portholes on the third deck were welded shut to enhance watertight integrity, and steel splinter shields around her 5 in (130 mm) and 1.1 in (28 mm) batteries were installed. Wasp was among 14 ships to be equipped with the early RCA CXAM-1 radar.[2] Once those repairs and modifications were completed, Wasp departed for the Virgin Islands on 22 March, arriving at St. Thomas three days later. She quickly moved to Guantanamo Bay to load maritime provisions for transport back to Norfolk.[1]

Upon returning to Norfolk on 30 March, Wasp conducted standard flight operations out of Hampton Roads in the following days, extending into April. In conjunction with Sampson, the carrier undertook an unsuccessful search for a downed patrol plane in her vicinity on 8 April. For the rest of the month, Wasp operated along the eastern seaboard between Newport, Rhode Island, and Norfolk, executing extensive flight and patrol missions with her embarked air group. Mid-May saw her relocation to Bermuda, where she anchored at Grassy Bay on the 12th. Eight days later, she set sail alongside heavy cruiser Quincy and destroyers Livermore and Kearny for exercises at sea before returning to Grassy Bay on 3 June. Wasp sailed for Norfolk three days later with destroyer Edison as her anti-submarine escort.

After a brief stay in the Tidewater area, Wasp returned towards Bermuda on 20 June. She and her escorts patrolled the Atlantic stretch between Bermuda and Hampton Roads until 5 July, as the Atlantic Fleet’s neutrality patrol zones expanded eastward. Arriving in Grassy Bay that day, she remained in port for a week before heading back to Norfolk, departing on 12 July alongside heavy cruiser Tuscaloosa and destroyers Grayson, Anderson, and Rowan.

Following her return to Norfolk on 13 July 1941, Wasp and her embarked air group carried out refresher training off the Virginia Capes. Meanwhile, the situation in the Atlantic had shifted, with the American involvement in the Battle of the Atlantic becoming imminent as the United States moved closer to involvement on the British side. To ensure American security and liberate British forces for other assignments, plans were made for the United States to occupy Iceland, in which Wasp played a crucial role.

Late in the afternoon on 23 July, while the carrier was docked alongside Pier 7, NOB Norfolk, 32 Army Air Forces (AAF) pilots reported on board “for temporary duty”. At 06:30 the following day, Wasp’s crew witnessed an intriguing cargo being loaded onto the ship by the ship’s cranes: 30 P-40Cs and three PT-17 trainers from the AAF 33rd Pursuit Squadron, 8th Air Group, Air Force Combat Command, stationed at Mitchel Field, New York. Three days later, four newspaper correspondents—including the distinguished journalist Fletcher Pratt—came on board.

The carrier had been assigned the mission of transporting these essential army planes to Iceland due to a shortage of British aircraft to support the American landings. The American P-40s would provide the requisite fighter cover to oversee the initial American occupying forces. Wasp proceeded out to sea on 28 July, accompanied by destroyers O’Brien and Walke as plane guards. The heavy cruiser Vincennes joined the formation later at sea.

Within a few days, Wasp’s group merged with the larger Task Force 16—composed of the battleship Mississippi, heavy cruisers Quincy and Wichita, five destroyers, the auxiliary Semmes, the attack transport American Legion, the stores ship Mizar, and the amphibious cargo ship Almaack. These vessels were also headed for Iceland with the first occupation troops embarked. On the morning of 6 August, Wasp, Vincennes, Walke, and O’Brien separated from Task Force 16 (TF 16). Shortly thereafter, the carrier turned into the wind and commenced launching the planes from the 33rd Pursuit Squadron. As the P-40s and the trio of trainers buzzed towards Iceland, Wasp headed back home to Norfolk, with her three escorts in tow. After another week at sea, the group returned to Norfolk on 14 August.

Wasp put to sea once more on 22 August for carrier qualifications and refresher landings off the Virginia capes. Two days later, Rear Admiral H. Kent Hewitt, Commander of Cruisers, Atlantic Fleet, moved his flag from the light cruiser Savannah to Wasp while the ships were anchored in Hampton Roads. Underway on the 25th, in company with Savannah and destroyers Monssen and Kearny, the aircraft carrier conducted flight operations in the following days. Rumors aboard suggested she was steaming out in search of the German heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper, reportedly prowling the western Atlantic for victims. On the 30th, those suspicions were confirmed for many when the British battleship HMS Rodney was sighted approximately 20 nautical miles (37 km; 23 mi) away, on the same course.

as the Americans.

In any case, if they were pursuing a German raider, they did not make contact with her. Wasp and her escorts anchored in the Gulf of Paria, Trinidad on 2 September, where Admiral Hewitt shifted his flag back to Savannah. The carrier stayed in port until 6 September, when she once again set sail on patrol “to uphold the neutrality of the United States in the Atlantic.”

While at sea, the vessel learned of a German U-boat unsuccessfully trying to attack the destroyer Greer. The U.S. had been increasingly drawn into the conflict; American warships were now escorting British merchant ships halfway across the Atlantic to the “mid-ocean meeting point” (MOMP).

Wasp’s crew anticipated returning to Bermuda on 18 September, but the new circumstances in the Atlantic necessitated a change in plans. Transferred to the cooler regions of Newfoundland, the carrier reached Placentia Bay on 22 September and refueled from the oiler Salinas the following day. The break in port was brief, however, as the ship got underway again late on the 23rd, heading for Iceland. In company with Wichita, four destroyers, and the repair ship Vulcan, Wasp arrived at Hvalfjörður, Iceland, on the 28th. Two days prior, Admiral Harold R. Stark, the Chief of Naval Operations, had ordered American warships to make every effort to destroy any German or Italian vessels they encountered.

With the heightened activity involved in the U.S. Navy’s conducting convoy escort missions, Wasp set out to sea on 6 October accompanied by Vincennes and four destroyers. These ships patrolled the foggy, frigid, North Atlantic until returning to Little Placentia Bay, Newfoundland on the 11th, anchoring during a fierce storm that battered the bay with strong winds and piercing spray. On 17 October, Wasp headed for Norfolk, patrolling along the way, and arrived at her destination on the 20th. The carrier soon departed for Bermuda and conducted qualifications and refresher training flights en route. Anchoring in Grassy Bay on 1 November, Wasp operated on patrols out of Bermuda for the remainder of the month.

October saw the incidents involving American and German warships multiplying on the high seas. The Kearny was torpedoed on 17 October, the Salinas on the 28th, and in the most tragic incident of that autumn, Reuben James was torpedoed and sunk with significant loss of life on 30 October. Meanwhile, in the Pacific, tension between the U.S. and Japan escalated with each passing day.

Wasp slipped out to sea from Grassy Bay on 3 December and met up with Wilson. While the destroyer acted as a plane guard, Wasp’s air group flew day and night refresher training missions. Moreover, the two vessels conducted gunnery drills before returning to Grassy Bay two days later, where she lay at anchor on 7 December 1941 during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.[1]

World War II

Atlantic Fleet

Wasp and the heavy cruiser Wichita in Scapa Flow.

Meanwhile, naval authorities experienced considerable anxiety that French warships in the Caribbean and West Indies were ready to break out and attempt to return to France. Consequently, Wasp, the light cruiser Brooklyn, and the destroyers Sterett and Wilson departed Grassy Bay and headed for Martinique. Faulty intelligence misled American authorities in Washington into believing that the Vichy French armed merchant cruiser Barfleur had set sail. The French were warned that the auxiliary cruiser would be sunk or captured unless she returned to port and resumed her internment. As it turned out, Barfleur had not departed after all, but had stayed in harbor. The tense situation at Martinique eventually eased, and the crisis dissolved.

With tensions in the West Indies significantly reduced, Wasp left Grassy Bay and headed for Hampton Roads three days before Christmas, in company with the Long Island, and escorted by the destroyers Stack and Sterett. Two days later, the carrier docked at the Norfolk Navy Yard to begin an overhaul that would last into 1942.

After departing Norfolk on 14 January 1942, Wasp navigated north and stopped at NS Argentia, Newfoundland, and Casco Bay, Maine. On 16 March, as part of Task Group 22.6 (TG 22.6), she made her way back toward Norfolk. During the morning watch the following day, visibility decreased significantly; and, at 06:50, Wasp’s bow struck the Stack’s starboard side, creating a hole and completely flooding the destroyer’s number one fireroom. Stack was detached and proceeded to the Philadelphia Navy Yard for repairs.

Meanwhile, Wasp entered port at Norfolk on the 21st without further incident. Shifting back to Casco Bay three days later, she set sail for the British Isles on 26 March, with TF 39 under the command of Rear Admiral John W. Wilcox, Jr., on the Washington. That force was intended to reinforce the Home Fleet of the Royal Navy. While en route, Rear Admiral Wilcox was swept overboard from the battleship and drowned. Despite being hindered by poor visibility conditions, Wasp aircraft participated in the search. Wilcox’s body was spotted an hour later, face down in the turbulent seas, but was not recovered due to the weather and heavy swells.[1]

Rear Admiral Robert C. Giffen, who flew his flag on the Wichita, took command of TF 39. The American vessels were met by a force centered around the light cruiser HMS Edinburgh on 3 April. Those ships escorted them to Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. While there, a Gloster Gladiator piloted by Captain Henry Fancourt of the Royal Navy accomplished the first landing of the war by a British aircraft on an American aircraft carrier when it touched down on Wasp.[citation needed]

While most of TF 39 joined the British Home Fleet — renumbered to TF 99 in the process — to cover convoys routed to North Russia, Wasp departed Scapa Flow on 9 April, destined for the Clyde estuary and Greenock, Scotland. The next day, the carrier sailed up the Clyde River, passing the John Brown Clydebank shipbuilding facilities. There, shipyard workers paused long enough from their tasks to give Wasp a rousing reception as she passed. Wasp’s forthcoming mission was critically important — one that would determine the fate of the island stronghold of Malta. That vital isle was being relentlessly attacked day after day by German and Italian aircraft. The British, facing the potential loss of air superiority over the island, requested the use of a carrier to transport planes that could reclaim air superiority from the Axis forces. Wasp was assigned ferry duty once again to take part in Operation Calendar, one of many Malta Convoys.

Spitfires and Wildcats aboard Wasp on 19 April 1942.

After landing her torpedo planes and dive bombers at Hatston in Orkney, Wasp loaded 47 Supermarine Spitfire Mk. V fighters of No. 603 Squadron RAF at Glasgow on 13 April and set off on the 14th, marking the beginning of “Operation Calendar.” Her screen consisted of Force “W” of the Home Fleet – a group including the battlecruiser HMS Renown and the anti-aircraft cruisers HMS Cairo and Charybdis. Madison and Lang also served in Wasp’s escort.

Wasp and her escorts passed through the Straits of Gibraltar under the cover of pre-dawn darkness on 19 April, evading detection by Spanish or Axis agents. At 04:00 on 20 April, Wasp identified 11 Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters on her deck and quickly deployed them to form a combat air patrol (CAP) over Force “W.” Meanwhile, the Spitfires were warming up their engines in the hangar deck spaces below. With the Wildcats patrolling above, the Spitfires were brought up one by one on the aft elevator, positioned for launch, and then given the command to take off. One by one, they roared down the deck and over the forward rounddown, until each Spitfire was airborne and heading toward Malta.

HMS Eagle accompanies Wasp on her second voyage to Malta.

Once the launch was complete, Wasp steered back toward Gibraltar, having safely delivered her

charges. Nevertheless, those Spitfires, which arrived to bolster the diminishing numbers of Gladiator and Hurricane fighters, were monitored by proficient Axis intelligence, and their arrival was precisely identified. Most of the Spitfires were obliterated by intense German aerial assaults that caught numerous planes stationary on the ground.

Consequently, it appeared that the critical situation necessitated a second ferry operation to Malta. Thus, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, apprehensive that Malta would be “pounded to bits,” requested President Roosevelt to permit Wasp to take “another good sting.” Roosevelt agreed. Wasp loaded an additional group of Spitfire Vs at King George V Dock Glasgow and departed for the Mediterranean on 3 May. Once more, Wasp proceeded without any interference. This time, the British carrier HMS Eagle accompanied Wasp, carrying her own group of Spitfires destined for Malta. The Spitfires for Eagle were loaded at Greenock, James Watt Dock, from lighters. This marked the beginning of Operation Bowery.

The two Allied carriers reached their launch sites early on Saturday, 9 May, with Wasp advancing in formation ahead of Eagle at a distance of 1,000 yards (910 m). At 06:30, Wasp initiated the launch of aircraft—11 Wildcats from VF-71 to serve as CAP over the task group. Initially, Eagle dispatched her 17 Spitfires in two waves; thereafter, Wasp launched an additional 47. The first Spitfire took off at 06:43, piloted by Sergeant-Pilot Herrington, but shortly after takeoff, it lost power and crashed into the sea, resulting in the loss of both pilot and aircraft. The other planes took off securely, assembling to fly towards Malta. An auxiliary fuel tank on another aircraft failed to deliver fuel; without the extra fuel, the pilot could not reach Malta and faced the options of landing on Wasp—without a tailhook—or ditching in the water.

Pilot Officer Jerrold Alpine Smith opted for the first choice. Wasp increased speed and retrieved the plane at 07:43. The Spitfire halted merely 15 feet (4.6 m) from the front edge of the flight deck, executing what one Wasp sailor described as a “one wire” landing. With her essential task completed, Wasp set course back to the British Isles, while a German radio station announced the shocking news that the American carrier had been sunk; on 11 May, Prime Minister Churchill sent a message to Wasp: “Many thanks to you all for the timely aid. Who claimed a wasp couldn’t sting twice?”[1]

Pacific Fleet

In early May 1942, nearly concurrently with Wasp’s second Malta mission—Operation Bowery—the Battle of the Coral Sea had taken place, followed by the Battle of Midway a month later. These confrontations reduced the U.S. to three carriers in the Pacific, making the transfer of Wasp crucial.

Wasp was hastily returned to the U.S. for modifications and maintenance at the Norfolk Navy Yard. During the carrier’s time in the Tidewater region, Captain Reeves—who had been elevated to flag rank—was succeeded by Captain Forrest P. Sherman on 31 May. Departing Norfolk on 6 June, Wasp sailed with TF 37, which consisted of the carrier and the battleship North Carolina, escorted by Quincy, San Juan, and six destroyers. The group transited the Panama Canal on 10 June, at which point Wasp and her consorts became TF 18, flying the two-star flag of Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes.

Arriving at San Diego on 19 June, Wasp took on the rest of her complement of aircraft, Grumman TBF-1 Avengers and Douglas SBD-3 Dauntlesses, the former replacing the older Vindicators. On 1 July, she departed for the Tonga Islands as part of the convoy for five transports carrying the 2nd Marine Regiment.

Meanwhile, preparations for an invasion of the Solomon Islands were underway to disrupt the Japanese initiative to establish a defensive perimeter around the boundaries of their “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.”

Wasp’s flight deck, 1942.

On 4 July, while Wasp was on her way to the South Pacific, the Japanese landed on Guadalcanal. Allied planners recognized that the Japanese operation of land-based aircraft from this key island would threaten Allied dominance in the New Hebrides and New Caledonia region. Plans were devised to expel the Japanese before their airfield on Guadalcanal became operational. Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley—having experience as a Special Naval Observer in London—was assigned to lead the operation; he established his headquarters in Auckland, New Zealand. With the Japanese having a foothold on Guadalcanal, time was critical; preparations for an allied invasion progressed with secrecy and urgency.

Wasp—alongside the carriers Saratoga and Enterprise—was designated to the Support Force under Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher. Under the tactical command of Rear Admiral Noyes, who was embarked on Wasp, the carriers were to provide air support for the invasion and the initiation of the Guadalcanal campaign.

Wasp and her aviators practiced day and night operations to sharpen their skills until Captain Sherman was confident that his aircrew could fulfill their mission. “D-day” had originally been set for 1 August, but the delayed arrival of certain transports carrying Marines pushed the date to 7 August.[1]

During the transit, Wasp’s engines posed a problem; a message sent on 14 July from CTF 18 to CINCPAC reported that she had encountered an issue with her starboard high pressure turbine, which was making a loud scraping noise at even the lowest speeds, limiting velocity to only fifteen knots on her port engine, thereby making air operations entirely reliant on favorable winds. The crew was undertaking repairs, including the removal of the turbine casing. Repairs to the rotor itself were planned for “BLEACHER” (Tongatapu, Tonga Islands),[4] where the destroyer tender USS Whitney (AD-4) was stationed, with an estimate of four days for the work required. Wasp arrived on 18 July for those repairs, and on 21 July (21 0802 July), CTF 18 reported that Wasp had successfully completed a trial, achieving speeds of twenty-seven knots with pre-casualty operations capable of twenty-five knots but with reduced reliability. Replacement blades available at Pearl Harbor and the replacement of all three rows of blades were advised after the ongoing operations were concluded.[1][5][6]

Wasp, escorted by the heavy cruisers San Francisco and Salt Lake City, along with four destroyers, steamed westward toward Guadalcanal on the night of 6 August until midnight. Then, she altered her course to the eastward to reach her launch position 84 nautical miles (97 mi; 156 km) from Tulagi one hour before dawn. Wasp’s first combat air patrol fighter took off at 05:57.

The initial flights of Wildcats and Dauntlesses were assigned specific targets: Tulagi, Gavutu, Tanambogo, Halavo, Port Purvis, Haleta, Bungana, and the radio station known as “Asses’ Ears.”

The Wildcats, commanded by Lieutenant Shands and his wingman Ensign S. W. Forrer, patrolled the northern coast towards Gavatu. The other two headed for the seaplane facilities at Tanambogo. The Grummans, arriving simultaneously at daybreak, caught the Japanese by surprise and strafed patrol planes and fighter-seaplanes in the vicinity. Fifteen Kawanishi H8K “Emily” flying boats and seven Nakajima A6M2-N “Rufe” floatplane fighters were obliterated by Shands’ fighters during low-altitude strafing runs. Shands was credited with four “Rufes” and one “Emily,” while his wingman, Forrer, received credit for three “Rufes” and an “Emily.” Lieutenant Wright and Ensign Kenton were credited with three patrol planes each and a motorboat servicing the “Emilys”; Ensigns Reeves and Conklin were each credited with two and shared one additional patrol plane. The strafing Wildcats also destroyed an aviation fuel truck and a vehicle loaded with spare parts.

Post-attack evaluations estimated that the antiaircraft and coastal battery sites identified by intelligence had been eliminated by the Dauntless dive bombers in their initial strike. None of Wasp’s aircraft was lost; but

Ensign Reeves, brought his Wildcat aboard Enterprise after depleting fuel levels.

At 07:04, Wasp dispatched 12 Avengers outfitted with bombs for targeting land objectives, led by Lieutenant H. A. Romberg. The Avengers neutralized opposition by bombing Japanese troop formations east of the land protrusion nicknamed Hill 281, in the Makambo-Sasapi area, and the facility on Tulagi Island.

Approximately 10,000 troops had landed during the initial day’s activities against Guadalcanal, encountering only minimal resistance. However, on Tulagi, the Japanese fought fiercely, retaining nearly one-fifth of the island by dusk. Wasp, Saratoga, and Enterprise – along with their protective screens – withdrew southward at nightfall.

F4Fs taking off from Guadalcanal, 7 August 1942.

Wasp fighters commanded by Lieutenant C. S. Moffett sustained an ongoing Combat Air Patrol over the transport zone until noon on 8 August. Simultaneously, a reconnaissance group of 12 Dauntlesses led by Lieutenant Commander E. M. Snowden scoured an area with a radius of 220 nautical miles (250 mi; 410 km) from their carrier, which included all of Santa Isabel Island and the New Georgia islands.

The Dauntless pilots had no contact with the Japanese during their two-hour flight; however, at 08:15, Snowden spotted a “Rufe” around 40 nautical miles (46 mi; 74 km) from Rekata Bay and shot the aircraft down using fixed .50 in (13 mm) machine guns.

Meanwhile, a significant formation of Japanese planes approached from Bougainville to assault the transports off Lunga Point. Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner instructed all transports to set sail and adopt a cruising formation. Eldridge was leading a squadron of Dauntlesses from VS-71 against Mbangi Island, near Tulagi. His rear-seat gunner, Aviation Chief Radioman L. A. Powers, mistakenly assumed the group of Japanese planes were friendly until six Zeroes attacked the first section with twelve unsuccessful firing passes.

Meanwhile, the leader of the final section of VS-71 – Lieutenant, junior grade Robert L. Howard – ineffectively engaged twin-engine Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” medium bombers aiming for the American transports, while being targeted by four Zeroes providing escort for the bombers. Howard downed one Zero with his fixed .50 in (13 mm) guns, while his rear gunner, Seaman 2nd Class Lawrence P. Lupo, impeded Japanese fighters attacking from the rear.

Wasp’s losses for the complete engagement on 7 and 8 August were:

- One fighter pilot, Ens. Thaddeus J. Capowski, missing in action after separating from the formation. His parents (Mr. and Mrs. Walter Capowski of Yonkers NY) were informed of TJC’s MIA status in early September 1942; shortly afterwards, TJC was located safe and unharmed.

- One scout bomber downed; pilot Lieut. Dudley H. Adams wounded by explosive ammunition and retrieved by Dewey; Radioman-gunner Harry E. Elliott, ARM3c, missing, reported killed before the crash.

- One fighter landed in the sea due to propeller issues; pilot rescued.

- One fighter crashed on the flight deck; pilot injured; aircraft was jettisoned overboard.

- One fighter collided with a barrier on the first day; repaired and flown on the second day.

The total aircraft losses for Wasp included 3 Wildcat fighters and 1 Dauntless scout bomber. In contrast, her aircraft destroyed 15 enemy flying boats, 8 floatplane fighters, and 1 Zero.

At 18:07 on 8 August, Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher recommended to Ghormley, at Nouméa, that the air support unit be withdrawn. Concerned with the substantial number of Japanese planes that had attacked on the 8th, Fletcher reported he had only 78 fighters remaining (initially he had 99) and that fuel for the carriers was dwindling. Ghormley accepted the recommendation, and Wasp joined Enterprise and Saratoga in retreating from Guadalcanal. By midnight, the landing had achieved its immediate goals. Japanese resistance – aside from a few snipers – on Gavutu and Tanombogo had been broken. Early on 9 August, a Japanese surface force engaged an American one in the Battle of Savo Island, departing with minimal damage after sinking four Allied heavy cruisers off Savo Island, including two that had served with Wasp in the Atlantic: the Vincennes and the Quincy. The early and unanticipated withdrawal of the support force, including Wasp, combined with Allied losses in the Battle of Savo Island, undermined the success of the operation in the Solomons.

After the initial day’s combat in the Solomons campaign, the carrier spent the following month engaged in patrol and protective operations for convoys and supply units headed for Guadalcanal. The Japanese began moving reinforcements to challenge the Allied forces.

Wasp was ordered south by Vice Admiral Fletcher for refueling and did not partake in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons on 24 August. After refueling on 24 August, Wasp hastened to the battle area. Her total aircraft inventory consisted of 26 Wildcats, 25 SBD Dauntlesses, and 11 TBF Avengers. (One SBD was earlier lost on 24 August due to ditching in the sea because of engine failure). On the morning of 25 August, Wasp initiated a search patrol. The SBD piloted by Lieut. Chester V. Zalewski shot down two Aichi E13A1 “Jake” floatplanes from the Atago (Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondō’s flagship). However, the SBDs reported no ships. The Japanese fleet had retreated beyond range. At 13:26 on 25 August, Wasp launched a search/attack operation comprising 24 SBDs and 10 TBFs against the convoy of Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka, which still seemed to be within range. Although the SBDs downed a flying boat, they couldn’t locate the enemy vessels anymore.

During the battle on 24 August, Enterprise was damaged and had to return to port for repairs. Saratoga was torpedoed a week later and departed the South Pacific conflict zone for repairs as well. This left only two carriers in the southwest Pacific: Hornet—which had been in service for only a year—and Wasp.

Loss

On Tuesday, 15 September 1942, the carriers Wasp and Hornet along with battleship North Carolina—with 10 other warships—were escorting the transports carrying the 7th Marine Regiment to Guadalcanal as reinforcements. Wasp had taken on the role of ready-duty carrier and was operating around 150 nautical miles (170 mi; 280 km) southeast of San Cristobal Island. Her fuel system was active, as planes were being refueled and rearmed for antisubmarine patrol missions; and Wasp had been in general quarters from an hour prior to sunrise until the morning search returned to the ship at 10:00. Thereafter, the vessel was in condition 2, with the air department at flight readiness. There was no engagement with the Japanese throughout the day, aside from a Japanese four-engined flying boat that was downed by a Wasp Wildcat at 12:15.

At approximately 14:20, the carrier turned into the wind to launch eight Wildcats and 18 Dauntlesses, as well as recovering eight Wildcats and three Dauntlesses that had been airborne since before noon. Lt. (jg) Roland H. Kenton, USNR, piloting an F4F3 from VF-71 was the last aircraft off the deck of Wasp. The ship promptly completed the recovery of the 11 planes, then turned easily to starboard, the vessel heeling slightly as the course change occurred. At 14:44 a lookout announced “three torpedoes … three points forward of the starboard beam.”

A spread of six Type 95 torpedoes were launched at Wasp at around 14:44 from the tubes of the B1 Type submarine I-19. Wasp quickly turned her rudder hard to starboard to evade the salvo, but it was too late. Three torpedoes impacted in quick succession around 14:45; one even surfaced, left the water, and struck the ship just above the waterline. All hit near the vessel’s fuel tanks and magazines. Two of the torpedoes passed ahead of Wasp and were seen moving past the stern of Helena before O’Brien was struck by one at 14:51 while maneuvering to evade the other. The sixth torpedo either passed astern or beneath Wasp, narrowly missing Lansdowne in Wasp’s screen around 14:48, and was noted by Mustin in North Carolina’s screen.

about 14:50, and impacted North Carolina around 14:52.[9]

Wasp engulfed in flames shortly after being torpedoed.

There was a swift series of detonations in the bow section of the vessel. Aircraft on the flight and hangar decks were tossed around and slammed onto the deck with such force that landing gears fractured. Planes suspended in the overhead hangar plummeted and crashed onto those on the hangar deck; fires ignited almost concurrently in the hangar and below decks. Soon, the heat from the raging gasoline fires ignited the stored ammunition at the forward anti-aircraft installations on the starboard side, showering debris across the bow of the vessel. The number two 1.1 in (28 mm) mount was blasted overboard.

Water systems in the forward section of the vessel had been rendered non-functional: there was no water accessible to combat the flames at the front, and the fires continued to trigger ammunition, bombs, and gasoline. As the ship listed 10-15° to starboard, oil and gasoline, expelled from the tanks due to the torpedo strike, ignited on the surface of the water.

Captain Sherman reduced speed to 10 knots (12 mph; 19 km/h), instructing the rudder to turn left to try to catch the wind on the starboard bow; he then went in reverse with a right turn until the wind was on the starboard quarter, attempting to control the blaze at the front. At that moment, flames rendered the central control station inoperable, and communication lines went silent. Shortly thereafter, a significant gasoline fire erupted in the forward section of the hangar; within 24 minutes of the initial assault, three more major gasoline vapor explosions occurred. Ten minutes later, Sherman made the decision to abandon ship, as all fire-fighting efforts were proving futile. The survivors needed to be evacuated swiftly to reduce fatalities.

After conferring with Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes, Captain Sherman commanded “abandon ship” at 15:20. All severely injured personnel were lowered into rafts or inflatable boats. Many uninjured crew members had to escape from the rear due to the intense flames at the front. The evacuation, as Sherman noted, appeared “orderly,” with no signs of panic. The only delays happened when numerous men hesitated to leave until all the wounded had been evacuated. The abandonment process took nearly 40 minutes, and at 16:00—assured that no one remained on board—Sherman left the vessel.

Although the threat from submarines caused the escorting destroyers to remain at a distance or adjust position, they conducted rescue operations until Laffey, Lansdowne, Helena, and Salt Lake City had 1,946 personnel on board. The flames on Wasp, drifting, moved aft and there were four fierce explosions at nightfall. Lansdowne was instructed to torpedo the carrier and remain on standby until she was sunk.[1] Lansdowne’s Mark 15 torpedoes had the same unrecognized defects reported for the Mark 14 torpedo. The first two torpedoes were launched flawlessly, but failed to detonate, leaving Lansdowne with only three remaining. The magnetic influence exploders on these were deactivated and the depth was set at 10 feet (3.0 m). All three detonated, but Wasp stayed afloat for a while, sinking at 21:00.[10] 193 men perished and 366 were injured during the attack. All but one of her 26 airborne aircraft successfully reached the nearby carrier Hornet before Wasp sank, but 45 aircraft were lost with the ship. Another Japanese submarine, I-15, duly noted and reported the sinking of the Wasp, while other US destroyers kept I-19 occupied avoiding 80 depth charges. I-19 escaped unscathed.[1][11]

Copyrighted by photolibrarian

Tagged: , USS Wasp (CV-7) , Aircraft Carrier

[qsm quiz=3]

[qsm_single_leaderboard ranks=”10″ order=”date_desc” average=”false” mlw_quiz=”3″ days=”0″]

an the other plugin:

[ays_quiz id=’2′]